Starting with the trade of materials from Europe in the late 18th century, Cherokee and other Southeastern Woodland fingerweaving thrived. The technique used, called open face or flat braiding, was typically done with one color of fine wool in an oblique pattern. Beads, usually white, were woven into the weaving making patterns along the oblique line. All weaving is 100% wool and glass size 10 or 11 European trade beads.

Regalia items

(bags, sashes, belts, garters, and straps)

(bags, sashes, belts, garters, and straps)

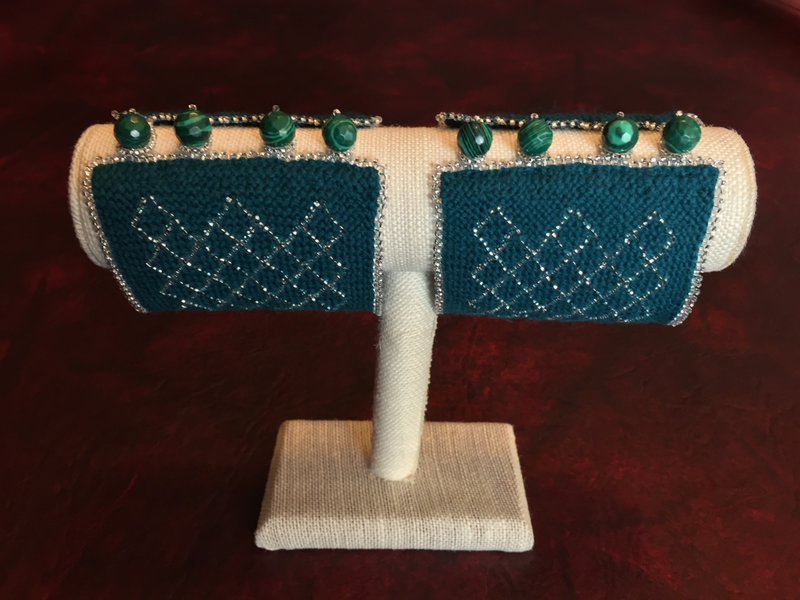

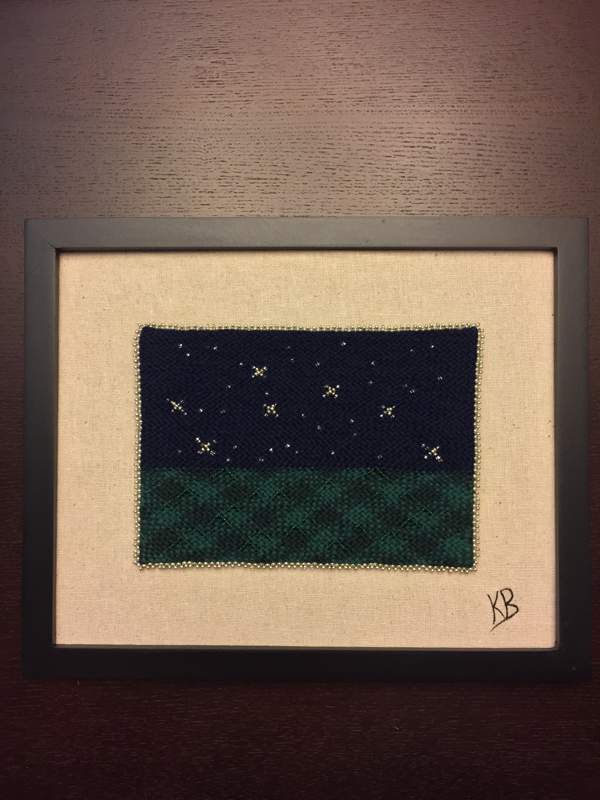

Modern items

(framed designs and jewelry)

(framed designs and jewelry)

|

Check out my YouTube channel for lessons and information about oblique fingerweaving!

|

Featured Works

See detailed images in above gallery.

|

The Forever War

This piece is dedicated to the soldiers who fight our wars only to come home from combat with invisible wounds, still engaged in a solitary and lifelong battle with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.The two-headed pileated woodpecker motif comes from pre-European contact mound builder pottery, and represents warriors, not generals or leaders, but the actual fighters of conflict. In Cherokee symbology, the color white represents peace whereas red represents war. I chose to weave the woodpecker in white surrounded by strips of red to represent the soldier who returns to civilian life, but is trapped by unending conflict. For these men and women who fight to defend human rights around the world, the battle doesn’t end when they return home. |

|

Jacobite Groom

This piece of Southeastern Woodland Fingerweaving is a statement of my heritage that holds a special place in my heart. Around the same time my Cherokee ancestors were doing this style of weaving, the Dress Act was being enforced in Scotland, prohibiting my Scottish ancestors from wearing the kilt and other traditional clothing. Many generations later, my rich family trees merged, and I enjoy merging their art forms. The colors I chose are from the Graham tartan. My Graham ancestors had to flee Scotland and reverse the spelling of their name, creating the Maharg family. I imagine a beautiful wedding with a Cherokee bride and Scottish groom. He would be proudly wearing a kilt, tartan, and brooch. |